On July 9, 1951, Hurston wrote in a letter to Florida historian Jean Parker Waterbury, “Somehow, this one spot on earth feels like home to me. I have always intended to come back here. That is why I am doing so much to make a go of it.”

It would be natural to assume that Hurston was writing about her hometown of Eatonville. Growing up in the oldest municipality in the United States entirely governed by African Americans instilled in Hurston a fierce confidence in her abilities and a unique perspective on race. Eatonville figures prominently in much of Hurston’s work, from her powerful 1928 essay “How It Feels To Be Colored Me” to her acclaimed 1937 novel Their Eyes Were Watching God.

But Hurston was not writing about Eatonville when she spoke of “the one spot on earth [that] feels like home to me” where she was “the happiest I’ve been in the last ten years” and where she wanted to “build a comfortable little new house” to live out the rest of her life. She was talking about Eau Gallie in Brevard County, about 17 miles south of Cocoa.

Zora’s Life in Brevard County

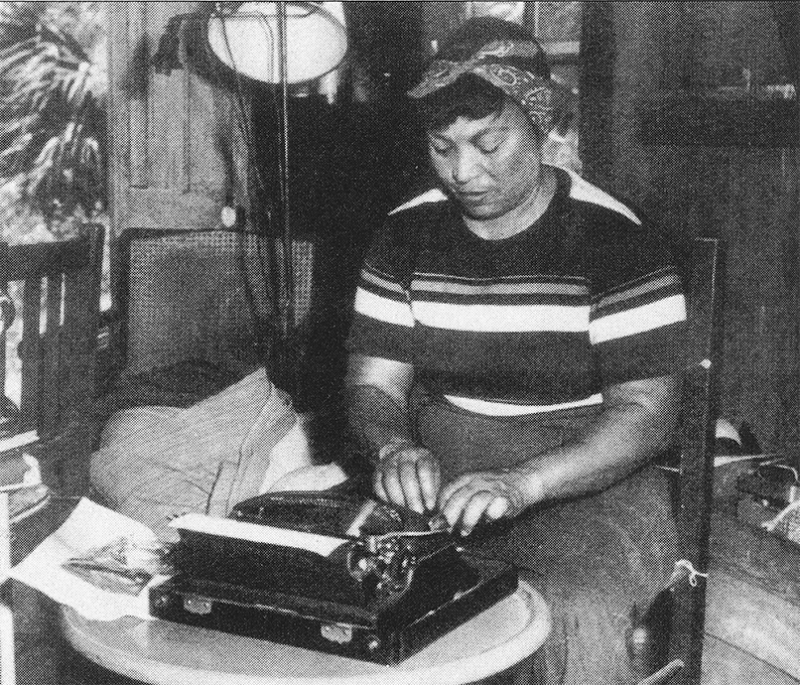

While author and anthropologist Zora Neale Hurston is often associated with her adopted hometown of Eatonville, she spent some of her happiest and most productive years in Brevard County. Hurston first moved to Brevard County in 1929 when she relocated to Eau Gallie and rented a cottage on the northeast corner of what is now the intersection of Guava Avenue and Aurora Road. While living there, she wrote the book of African American folklore Mules and Men (published in 1935). She also documented research she had done in Florida and New Orleans, and she worked on some of her theatrical pieces.

In the 1940s and early 1950s, Hurston spent time traveling, writing, and working in North Carolina, South Carolina, St Augustine, Honduras, the Bahamas, and Miami. Hurston returned to Eau Gallie in 1951, moving into the same cottage where she had lived years earlier. While living there, she staged a concert at Melbourne High School, its first integrated event. She also worked on a project that became her passion, the manuscript for Herod the Great, a different interpretation of the Bible's King Herod. Her manuscript was never published.

In 1952, Hurston traveled to Live Oak and covered the murder trial of Ruby McCollum, a Black woman who killed her white abuser. In 1953, she wrote an editorial for the Orlando Sentinel arguing against the Brown v. Board of Education decision. Her controversial disapproval of public school integration reflected her belief in the need to preserve African American culture and communities.

While working as a librarian at the Technical Library for Pan American World Airways on Patrick Air Force Base, Hurston was forced to leave her Eau Gallie cottage because she could no longer afford it. In 1956, she moved to an efficiency apartment in nearby Cocoa.

Moving On to Fort Pierce

Hurston was fired from her job at Patrick Air Force Base in May 1957 for being “too well-educated for the job.” She then left Brevard County and became a columnist for the Fort Pierce Chronicle. In 1958, she took a teaching position at Lincoln Park Academy. In 1959, she suffered a series of strokes and applied for welfare. Hurston died in Fort Pierce in 1960 at the age of 69. At the time of her death, her books were out of print and she was living in poverty in a welfare home.

In 1973, author Alice Walker renewed interest in Hurston’s work when she discovered her unmarked grave in Fort Pierce at the Garden of Heavenly Rest. Ms. Magazine published Walker's essay, "In Search of Zora Neale Hurston," in 1975. Walker also edited "I Love Myself When I Am Laughing . . . and Then Again When I Am Looking Mean and Impressive: A Zora Neale Hurston Reader" in 1979. Alice Walker bought a gravestone for Zora Neale Hurston. Her epitaph reads, “Zora Neale Hurston: A Genius of the South.”

Zora Neale Hurston’s Legacy

Each year since 1990, the Association to Preserve the Eatonville Community has presented the Zora Neale Hurston Festival of the Arts and Humanities, also known as ZORA! Festival. Zora Festival is named in honor of the American author, anthropologist, and folklorist Zora Neale Hurston and takes place in Hurston’s hometown of Eatonville, Florida. The weeklong Zora Festival is inspired by Zora Neale Hurston’s celebration of black culture, history, and life.